- Feb 24, 2025

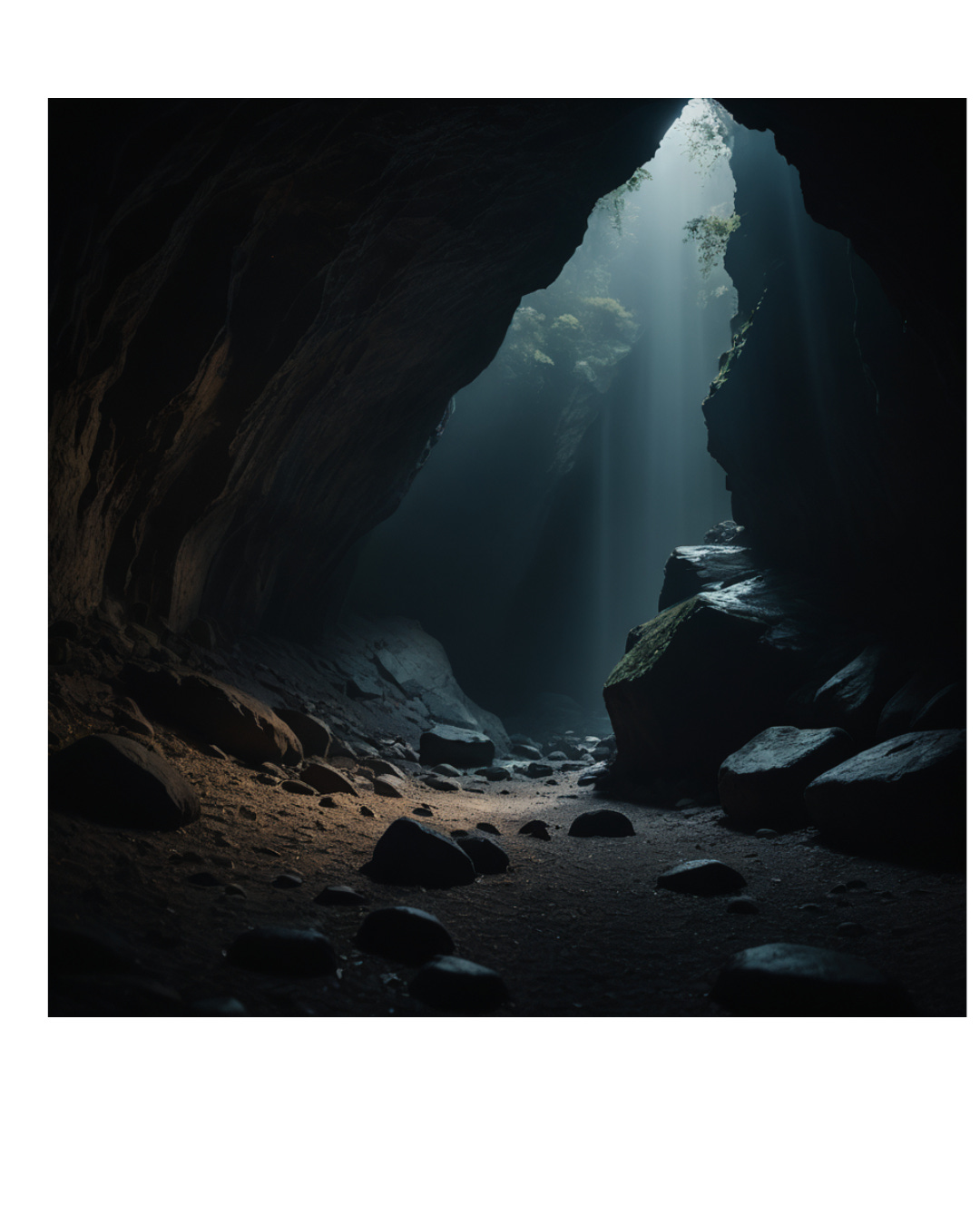

My One Companion is Darkness

- Karl Schudt

- 0 comments

Psalm 88 is a prayer of desolation and abandonment. It concludes with “My one companion is darkness,” which seems to be a cry of the complete loss of God. But is it?

Who is this God person anyway?

Soulsteading is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribed

In Christianity, God is not another part of the universe, another creature. In Hesiod and Homer, Zeus is a part of the whole, and you can ask about his origins. The God of Christianity precedes the story. He’s there right at the first verse of Genesis. Zeus comes later in Hesiod’s cosmogony, part of an already-existing universe.

So, God is completely other. As Thomas Aquinas puts it, every creature is created, which means it is in potency to being. Everything that you know receives being from another. God is being itself. God is really weird, being uncreated.

All knowledge comes through the senses

Everything you know started in your senses. You use some sort of comparison and classify things. You say, for example, “that’s a big dog!”. Whatever it is shares in dogness and bigness. It is similar to other dogs and big things. How do these categories work when applied to a non-sensible thing? Can you say “God is big” and not make an error?

In fact you can’t. Is God big? Perhaps in a sense, but He is also small. God is good. Yes, of course! But pizza is good. In what way is God like a pizza? It’s not so simple to figure it out!

What God is not

The essence of God, being completely unlike anything created, is therefore inaccessible to us. St. Thomas Aquinas says in the introduction to the Summa Theologiae “We cannot know what God is, but only what He is not. So to study Him, we study what has not, such as composition and motion.”

This is apophatic theology, where you say that God is unlimited (without limit), omniscient (without limit of knowledge), omnipotent (without limit of power), or omnibenevolent (without limit of love). In such theology, you take away anything in your concept of God that is characteristic of creatures.

St. Thomas describes this in ST:13.1:

in this life we cannot see the essence of God; but we know God from creatures as their principle, and also by way of excellence and remotion.

Excellence: whatever is good is applied to God, but in a more excellent way. Pizza is good, but God is better.

Remotion: by removing that which only applies to creatures. Pizza is good in that it temporarily satisfies our appetite. God is good in that He satisfies eternally.

Feelings are not God

How does this apply to the psalm?

Some people are blessed with religious feelings. They go to church and leave in happy tears at the beauty of it all. They feel an almost bodily consolation at the thought of God.

I have never been such a person! Perhaps I’m immune to dopamine. Whatever it is, I don’t usually feel it.

In defense of me: at some point in one’s spiritual development, you have to get rid of the sensations. You have to realize that the warm fuzzies that you feel are not God.

In the Western mystical tradition, great saints such as John of the Cross and Theresa of Avila have warned of this. If you progress far in the mystical life, at some point God turns off the spigot.

St. Gregory Palamas says that God is beyond negation, and that “it is no longer the sacred symbols accessible to the senses that it contemplates, nor yet the variety of Sacred Scripture that it knows; it is made beautiful by the creative and primordial beauty, and illumined by the radiance of God.”

At some point, if you are progressing, you need to let go of childish things.

My one companion is Darkness

Look back at Psalm 88. Pray with the psalmist: “Why do you reject my soul, Lord, and hide your face from me?” Perhaps this divine absence is an act of love from God, so that you will realize that “my only friend is Darkness,” that God is always with you, even when all is desolate.

It’s more cheerful that way, isn’t it?